RAJENDRA SINGH

RAJENDRA SINGH

THE “WATERMAN OF INDIA”

Stockholm Water Prize / Ramon Magsaysay Award winner

- Subbu

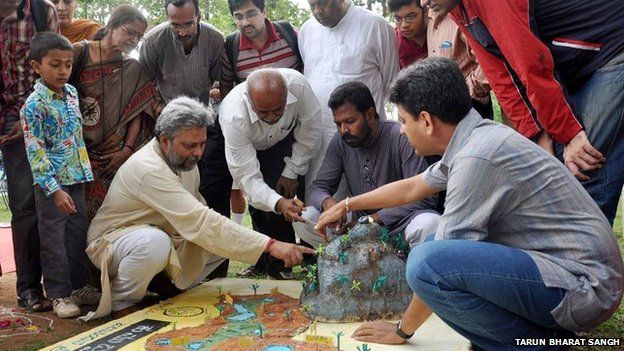

Rajendra Singh (born 6 August 1959) is a well-known water conservationist from Alwar district, Rajasthan in India. Also known as "waterman of India", he won the Stockholm Water Prize, an award known as "the Nobel Prize for water", in March 2015. Previously, he won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for community leadership in 2001 for his pioneering work in community-based efforts in water harvesting and water management. He runs an NGO called 'Tarun Bharat Sangh' (TBS), which was founded in 1975.

Rajendra Singh (born 6 August 1959) is a well-known water conservationist from Alwar district, Rajasthan in India. Also known as "waterman of India", he won the Stockholm Water Prize, an award known as "the Nobel Prize for water", in March 2015. Previously, he won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for community leadership in 2001 for his pioneering work in community-based efforts in water harvesting and water management. He runs an NGO called 'Tarun Bharat Sangh' (TBS), which was founded in 1975.

Rajendra has done lot of works over the years to help people in India to revive their watershed, and in turn return to their traditional ways of life. He started this career with no real knowledge of water conservation methods.

Rajendra had two influences in his early life that inspired him to get involved in helping small villages get back to their traditional way of life. The first came in 1974 when Rajendra was still in high school. One day Ramesh Sharma, a member of Gandhi Peace Foundation, visited his town and started trying to make improvements. He cleaned up the town, opened a vachnalaya (library), and helped to settle local conflicts. Soon after this he invited Rajendra to help him with an alcoholism rehabilitation center. It was during this time that they grew to be good friends and Rajendra learned much from him about helping people.

The second influence was a man named Pratap Singh who was an English language teacher at Rajendra’s school. Pratap would talk with his students after class about politics and social issues, and this made Rajendra start thinking independently about his government and what they were doing with India. These two influences started Rajendra down a path that would change his life and the lives of many people around him.

The second influence was a man named Pratap Singh who was an English language teacher at Rajendra’s school. Pratap would talk with his students after class about politics and social issues, and this made Rajendra start thinking independently about his government and what they were doing with India. These two influences started Rajendra down a path that would change his life and the lives of many people around him.

After graduating college and being involved with a number of student groups Rajendra started looking at how traditional, community based, water harvesting and management methods could help people in the semi-arid regions of India. India has not always been so dry, so there must be a way to bring the water back, and Rajendra found out how to do that. Through a number of traditional techniques and structures he has brought water back to regions that were dry for years, and has brought rivers back to life after decades of being dry.

One of the most popular structures that are built called johad’s. A johad is a type of rainwater storage tank that is built on the ground out of anything from dirt and stone to concrete. The Johad stores water collected during the rainy season so that it can be used for human or animal consumption throughout the year. Another thing that is great about johads is that they help to replenish groundwater. When you have a body of water that is collected, whether it is in a johad, a pond, or a lake the water slowly percolates into the ground and replenishes groundwater supplies. Another similar structure that Rajendra uses is called the check dam. It’s fairly similar to the johad except that instead of collecting rainwater the check dams are set up across streams or small rivers and form pools. These dams can also be made out of a number of materials; dirt, rocks, logs, basically anything that will hold back water. These dams are good for local populations because they don’t completely stop the flow of water, just make pools that then overflow and keep moving downstream. These pools of water then replenish groundwater supplies in the same way that the johads do. When you take an area that has been through several years of dought and has no groundwater and set up several if not dozens of these structures it’s amazing what can happen.

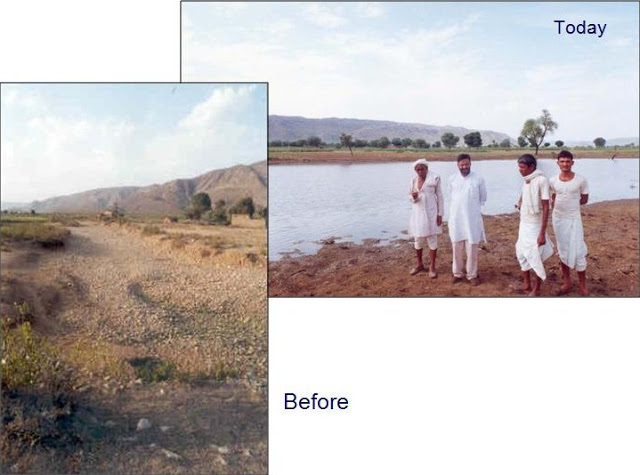

One of the most popular structures that are built called johad’s. A johad is a type of rainwater storage tank that is built on the ground out of anything from dirt and stone to concrete. The Johad stores water collected during the rainy season so that it can be used for human or animal consumption throughout the year. Another thing that is great about johads is that they help to replenish groundwater. When you have a body of water that is collected, whether it is in a johad, a pond, or a lake the water slowly percolates into the ground and replenishes groundwater supplies. Another similar structure that Rajendra uses is called the check dam. It’s fairly similar to the johad except that instead of collecting rainwater the check dams are set up across streams or small rivers and form pools. These dams can also be made out of a number of materials; dirt, rocks, logs, basically anything that will hold back water. These dams are good for local populations because they don’t completely stop the flow of water, just make pools that then overflow and keep moving downstream. These pools of water then replenish groundwater supplies in the same way that the johads do. When you take an area that has been through several years of dought and has no groundwater and set up several if not dozens of these structures it’s amazing what can happen. One of Rajendra’s earliest ventures was in the Alwar district. At that time most parts of the district were considered “dark zones” which meant they had little or no groundwater left. The way of life for people in these villages had changed drastically when over the years their ponds and rivers dried up leaving them with no way to make a living. Traditionally men had farmed this land, but now they had to head to the city and get jobs so that they could provide for their family. If there was water for farming there before there could be water again, and Rajendra knew this. He started constructing johads throughout the district with the help of local villagers, and soon there were more than he could count. As planned, the johads filled with water during the rainy season and held onto it. 15 years later water has been restored and life is back to normal for the people of the Alwar district. This success led the TBS to work with hundreds of other villages and help them to bring back the water they once had. Although it took 15 years these people now have a sustainable way to keep their groundwater levels high which will allow them to farm and keep their villages alive for centuries to come.

One of Rajendra’s earliest ventures was in the Alwar district. At that time most parts of the district were considered “dark zones” which meant they had little or no groundwater left. The way of life for people in these villages had changed drastically when over the years their ponds and rivers dried up leaving them with no way to make a living. Traditionally men had farmed this land, but now they had to head to the city and get jobs so that they could provide for their family. If there was water for farming there before there could be water again, and Rajendra knew this. He started constructing johads throughout the district with the help of local villagers, and soon there were more than he could count. As planned, the johads filled with water during the rainy season and held onto it. 15 years later water has been restored and life is back to normal for the people of the Alwar district. This success led the TBS to work with hundreds of other villages and help them to bring back the water they once had. Although it took 15 years these people now have a sustainable way to keep their groundwater levels high which will allow them to farm and keep their villages alive for centuries to come.

In 1986 when Rajendra and the TBS got to the Arvari River it had been dry for decades. They looked at the situation around the river, or what used to be a river, and thought that they maybe there was something that they could do about it. The people of one of the local villages, with help from the TBS, went to what used to be the source of the river and built a johad, soon after people from this and nearby villages started building small earthen dams along the riverbed and catchment area. When they reached the point where they had built 375 of these dams the river started flowing again! They had replenished the groundwater to the point that water was staying at the surface and once again the Arvari was flowing. Rajendra said that “It was not our intention to re-create the river, for we never had it in our wildest dreams”. By using traditional harvesting methods they were able to revive a river to what it was decades ago. And this isn’t the only river. The Ruparel, Sarsa, Bhagani and Jahajwali all went from being dry for decades to flowing once again.

Besides being a guru of traditional rainwater harvesting techniques Rajendra has also become very involved in politics. One of his earlier experiences that led to this had to do with mining. Rajendra and the TBS were working in the Project Tiger Sanctuary of Sariska building johads to help bring their ponds and lakes back to what they once were, but after some time they noticed that the water levels were staying the same. They thought about this for a while and Rajendra eventually realized that it was because of the mining that was going on nearby. What was happening was that huge pits were dug while the mining was going on, but once the mining was done they didn’t spend time filling the hole back up with dirt and rock, and instead over time they filled with rainwater. Because these pits were so big they collected most of the rainwater and so the groundwater never got replenished and the ponds and lakes stayed dry. Once they realized this they took the issue to the government which eventually led to the closure of 470 mines in the sanctuary and around its borders. This didn’t come without its consequences; including Rajendra being beaten by people involved with the mining operations, but that wouldn’t stop him. In 1991 the TBS went to the Supreme Court with a public interest petition and got mining banned in the wider Aravallis area, and in 1992 mining was banned by the Ministry of Environment and Forest in the Aravalli hill system.

Besides being a guru of traditional rainwater harvesting techniques Rajendra has also become very involved in politics. One of his earlier experiences that led to this had to do with mining. Rajendra and the TBS were working in the Project Tiger Sanctuary of Sariska building johads to help bring their ponds and lakes back to what they once were, but after some time they noticed that the water levels were staying the same. They thought about this for a while and Rajendra eventually realized that it was because of the mining that was going on nearby. What was happening was that huge pits were dug while the mining was going on, but once the mining was done they didn’t spend time filling the hole back up with dirt and rock, and instead over time they filled with rainwater. Because these pits were so big they collected most of the rainwater and so the groundwater never got replenished and the ponds and lakes stayed dry. Once they realized this they took the issue to the government which eventually led to the closure of 470 mines in the sanctuary and around its borders. This didn’t come without its consequences; including Rajendra being beaten by people involved with the mining operations, but that wouldn’t stop him. In 1991 the TBS went to the Supreme Court with a public interest petition and got mining banned in the wider Aravallis area, and in 1992 mining was banned by the Ministry of Environment and Forest in the Aravalli hill system.

Since 1985 Rajendra and the TBS have built 4,500 johads, to collect rainwater in some 850 villages in 11 districts in India, and there is no indication that they’re going to slow down anytime soon. Besides the fact that he’s giving people their livelihood back the people in these villages now understand how to keep a plentiful supply of groundwater at all times, and if needed how to get more. Along with being able to build and maintain the johads the villagers can now pass these skills onto future generations to ensure the survival of their traditional way of life. Rajendra has dedicated his life to water, and has helped thousands of people return to a way of life they have had for centuries but were close to losing.

****************************